E.D. Notes For the Field: How to Talk to Your Funders About Your Crisis

As a nonprofit E.D., you’ve been entrusted with leading a complex entity — a nexus of clients/constituents, board members, staff, perhaps volunteers, programming methodologies, facilities, money, and of course politics. It’s never easy, and most people are not cut out for this role, but you are. It takes a person with the drive to lead and the tenacity to stick with it through many ups and downs. That’s why you applied, and that’s why the board selected you. It’s a challenging role, especially now, when so many nonprofits are facing significant headwinds, even crises.

Adding to your troubles is this question – How should I talk to my funders about our crisis? To begin, let’s state the obvious: despite so many funders’ best efforts, this relationship is not one of equals. To put it plainly: they have the money, you need it. This power imbalance leads to a natural reluctance to be fully candid with people (and remember funders are first and foremost people) who in times of crisis literally make life and death decisions for your organization.

With everything that is coming at you each day, you look for patterns, eager for insight into what might be coming down the road. For example, the budget usually gets decided in summer, after your major public funders finalize their decisions; or you always have a cashflow crunch in December, but it eases by February; or you add a new group of board members in January, followed by the annual retreat. These patterns become clearer after a couple of years in the role while your first year at the helm can seem like an unending succession of surprises.

But what do you do when the patterns are broken? When political upheaval leads to financial insecurity and there’s no end in sight? That’s chaos, and that’s what many E.D.s are facing today. In fields as diverse as public media, arts and culture, environment, health, human services, and legal advocacy, unexpected, often contradictory, illegal, or plain nonsensical edicts seem to come daily from the White House. These are then translated into policies that create chaos for your organization and the people or causes you serve. Sound familiar?

Here’s a sample of questions we are hearing from E.D.s facing crises:

- How do I tell my program officer that without a supplemental grant we are likely to go under in the next six months?

- Will talking about a potential downsizing, program spinoff, or merger weaken my standing with major donors? Will they think I’m not up to the job?

- I’ve dipped into a restricted grant to cover payroll. I thought I could repay it by now but that’s looking doubtful. What do I tell the foundation?

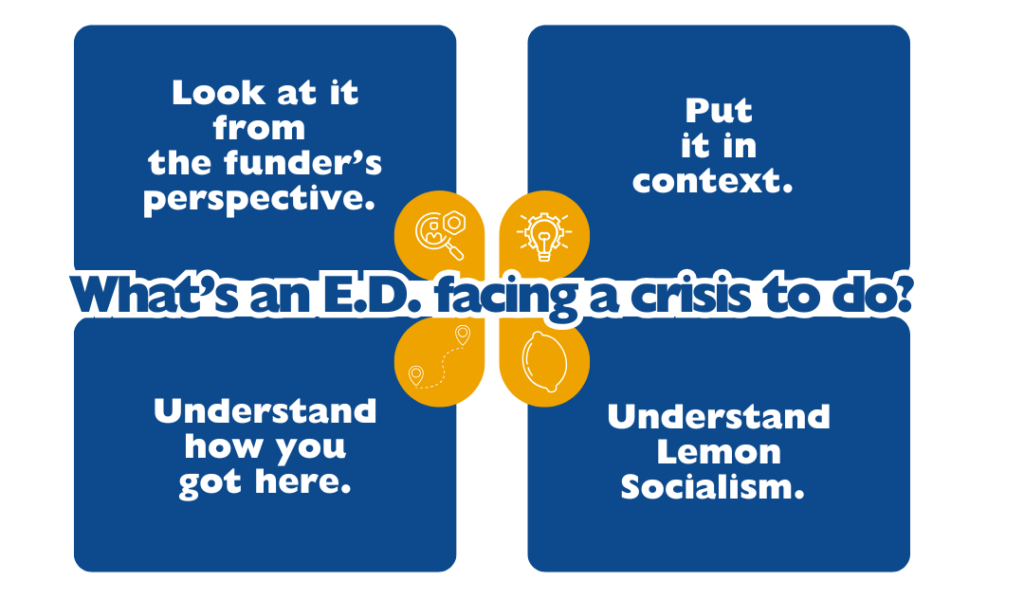

These are serious questions, but they are nothing new. However, the current chaos gives them new urgency. What’s an E.D. facing a crisis to do?

- Look at it from the funder’s perspective. First, reverse the lens and consider your funder’s circumstances, outlook, and needs. Is the funder a program officer who wants to both advance the foundation’s mission and look good to their boss? Is the donor a high-net-worth individual who made their fortune taking risks and maybe only after a failure? Or, is the funder a risk-averse family that is scared off by bad news? Knowing the funder’s needs will help you frame your message.

- Put it in context. Remember that you are not alone in this. Entire fields are under attack, and funding sources worth hundreds of millions are on hold, cancelled, even clawed back. Putting your situation in this context — while not hiding your own missteps — helps your funder to see this crisis for what it is: widespread, deep, and unprecedented.

- Understand how you got here. What decisions did you make, or fail to make, that contributed to the problem? During the Racial Reckoning in 2020 – 2022, did you overextend, believing (or hoping) the new infusion of funding would continue indefinitely? Did you go too far in offering new employee benefits you might not be able to sustain? Again, if you made any of these decisions, you did so in good faith. So did many other organizations.

- Understand Lemon Socialism. In America, any activity that can be done for profit, generally is; while any socially necessary activity that is unlikely to generate sufficient revenue (a “lemon”) is likely done by a nonprofit with funding through government contracts, private philanthropy, or both. It is therefore unfair to criticize a nonprofit for not “acting like a business.” The social sector is designed to undertake socially valuable activities that business won’t. Homeless shelters cannot make ends meet by charging hotel-level fees, cancer research cannot advance by charging patients a million dollars to participate in a drug trial, and immigrant advocates cannot support their staff through fees charged to their undocumented clients.

With this context in mind, remember that your relationship with your funders is just that — a relationship — and relationships are built on candor. Think of your funder — despite the power imbalance — as a partner. Remember, funders can only achieve their goals through you and other grantees. They need you as much as you need them. If you’ve built a trusting relationship, now’s the time to test that trust. If you have a more transactional relationship, now’s the time to begin building trust.

As in most situations we face in organizational life, the phrase “Don’t bring me problems, bring me solutions,” is apt. So, before you approach your funders, do a thorough analysis of your situation. Be ready to honestly and succinctly explain:

- This is where we are.

- This is how we got here.

- Here are two or three alternatives we’ve identified to address it.

This last point is critical. Funders are accustomed to grantees approaching them with a variety of problems but only one solution: write us a big check. This approach threatens your credibility. On the other hand, you might try an approach I used decades ago when a capital project largely funded by our county government ran over budget.

I told our contact at the County, “We planned carefully but a combination of factors led to a 20% increase in costs. I’ve raised a third of our budget from private sources but at this point those avenues are exhausted. We can terminate the project, leaving us with a bit of a mess and without the completed building we all want; we can try to redesign and downsize the project but I’m not sure how much that will save or how long it will take; or the County can help us by covering the shortfall. Maybe you have other ideas?”

The County Administrator looked at the projections I provided and said, “I think you could have maybe managed this project a little better and avoided this overrun, but here we are. We need that building, so we’ll find a way to cover the shortfall.”

The criticism hurt, and may or may not have been justified, but giving the funder alternatives, including two that I hated but didn’t cost them more money, bought enough credibility to continue the partnership.

Your leadership is most sorely tested in the darkest of times. Engaging your funders as partners will give you the best opportunity to navigate the chaos. Working together, both funders and nonprofits can weather this crisis, ensuring we make the best decisions in an untenable situation.

Comment section

1 thought on “E.D. Notes For the Field: How to Talk to Your Funders About Your Crisis”